[ad_1]

Electronics are all over the place—not simply telephones and computer systems, but in addition smartwatches, toothbrushes, e-bikes, toys, energy instruments, furnishings with built-in USB ports, and even sensible bogs with Wi-Fi connectivity. When this stuff are tossed, they turn out to be e-waste, a poisonous sort of trash that has been surging lately—and which the world is ill-equipped to recycle.

In 2022, the world generated a report 62 million tonnes of e-waste—an quantity that will fill 1.55 million 40-tonne vehicles, sufficient to wrap across the equator—in keeping with the Global E-Waste Monitor 2024, a brand new report from the United Nations. (That’s up from 53.6 million tonnes in 2019, per the last UN report.) And that waste is predicted to continue to grow: it’s rising globally by 2.6 million tonnes a 12 months.

[Image: Global E-Waste Monitor 2024]

However recycling isn’t maintaining. In 2022, simply 22.3% of all international e-waste was correctly collected and recycled; total, the quantity of e-waste is rising 5 instances quicker than the speed of documented e-waste recycling. “That is one thing that actually worries me,” says Kees Balde, lead creator of the report and senior scientific specialist on the UN Institute for Coaching and Analysis. “There may be numerous discuss [e-waste], however we want extra motion.” And as e-waste grows, its recycling charge is predicted to drop: the report expects international e-waste assortment and recycling to drop to twenty% by 2030.

Recycling sorting Germany [Photo: R. Kuehr/UNITAR]

Recycling at massive is broken, however e-waste is a matter that wants explicit consideration, consultants say, partially due to its distinctive challenges. “Every machine accommodates hazardous supplies and invaluable supplies,” Balde says. “We should make certain that the hazardous supplies are safely dismantled and disposed of, and that the dear supplies are being recycled, in order that we will reclaim the out there valuable supplies . . . which can also be not simple to do. If it have been simple, the markets can be already doing it.”

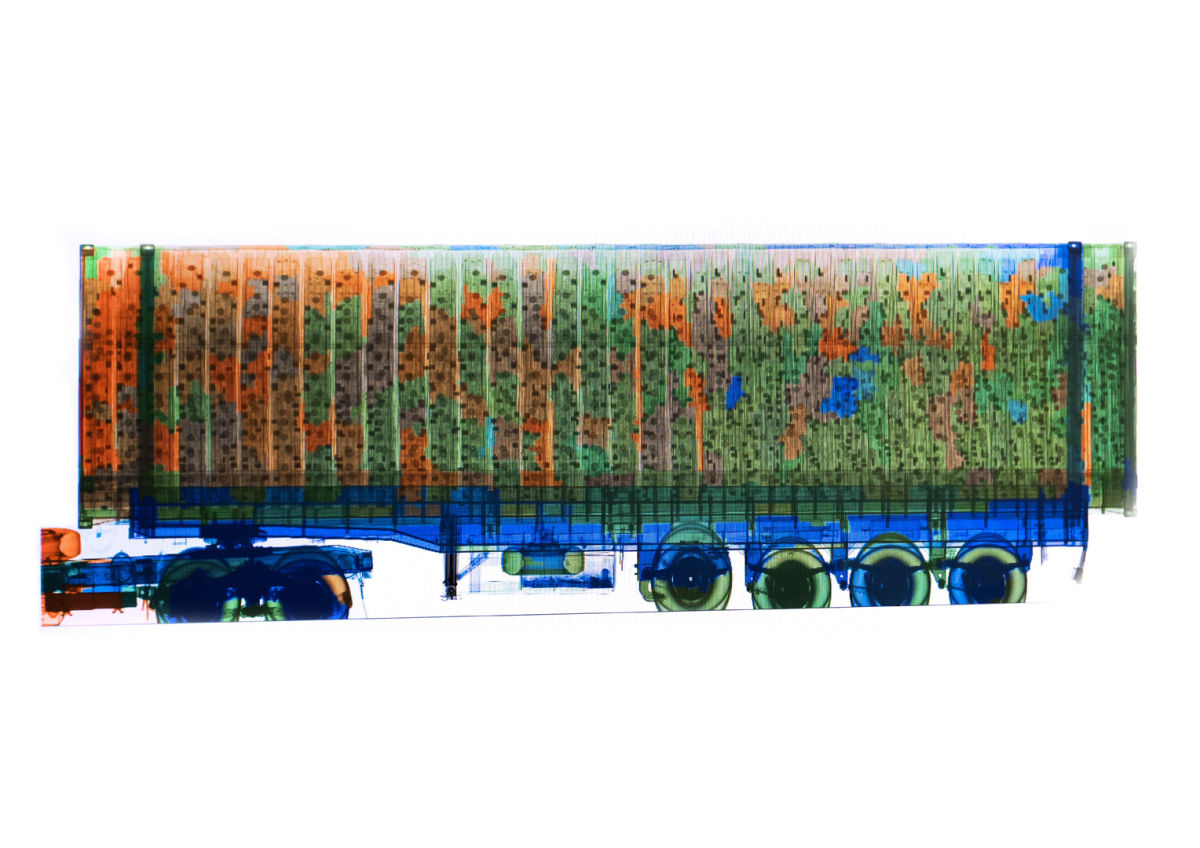

GHANA, Accra, Tema, 2023. X-ray picture captured from the display of Ghanaian customs within the port of Tema. Press photographs Captions-T&C

The picture reveals sound methods piled up. The varied colours point out the assorted parts that compose the load. [Image: © Bénédicte Kurzen/Fondation Carmignac/NOOR]

These hazardous supplies embody mercury; when electronics aren’t correctly recycled, the poisonous chemical substances can leach into the soil, water, and air, damaging the setting and threatening human well being. In the meantime, each steel not collected from recycled e-waste means extra new metals that need to be mined for electronics, which include their very own disastrous environmental and social impacts. The UN report discovered that e-waste in 2022 contained $92 billion price of metals like copper, gold, and iron.

Outdated Fadama, Accra, Ghana, in February 2023. Regionally collected end-of-life cell phones offered for elements and recycling. [Photo: © Muntaka Chasant for Fondation Carmignac]

On the subject of taking motion on e-waste, Balde says laws will probably be key. “We have to have the ample [funding] and legislative push from governments and producers which might be chargeable for the waste that they’re producing.” As of 2023, 81 international locations had some type of e-waste laws, up from 78 in 2019. And that has made a distinction. Nations with laws have, on common, a 25% assortment and recycling charge, “whereas the vast majority of those who don’t have laws are near 0%,” says Garam Bel, round economic system coordinator on the Worldwide Telecommunication Union, a specialised UN company concerned with the report. “For me, that tells a robust story.”

Within the U.S., there’s no federal laws on e-waste, however 25 states plus D.C. have electronics recycling legal guidelines, and 27 states have “right to repair” legal guidelines. The European Union, alternatively, has each an electronics recycling and restoration regulation and a right to repair directive. Each areas have recycling charges over 40%, however the report authors notice that the EU’s laws is stronger, because it bans exporting e-waste to non-OECD international locations, which lack the infrastructure to handle this waste.

However laws can’t be the only real answer. In some circumstances, it’s poorly enforced or contains no monetary funding in recycling methods. Balde provides that many digital units merely aren’t designed to be repaired or recycled. In these circumstances, laws and improved recycling expertise nonetheless wouldn’t have the ability to reclaim the metals.

Outdated Fadama in Accra, Ghana. Latif Fuseini, a repairman, makes an attempt to restore and reanimate end-of-life electrical motors (from air conditioners, washing machines, and so on.). Utilizing fan blades from these units, he redesigns the motors into ceiling followers, that are used extensively in Outdated Fadama and Northern Ghana. He depends on the end-of-life waste stream as a supply of elements. [Photo: © Muntaka Chasant for Fondation Carmignac]

On this manner, the businesses and producers behind electronics even have a job to play. Huge tech, Balde notes, makes huge income, “and they need to additionally take a accountability, in my opinion, to arrange restore schemes to forestall e-waste.” Corporations might additionally make their products easier to recycle, like by designing modular electronics, in addition to establishing monetary mechanisms with cities to higher separate e-waste and ship it to the suitable recyclers. “Producers are taking part in a pivotal function in all of this.”

Although the information about e-waste on this newest report are stark, Balde hopes it spurs individuals to take motion. “By having the information on the desk, we set a degree taking part in subject,” he says,” and as a foundation of that, those who’re chargeable for making the change can begin making the change.”

[ad_2]

Source link