[ad_1]

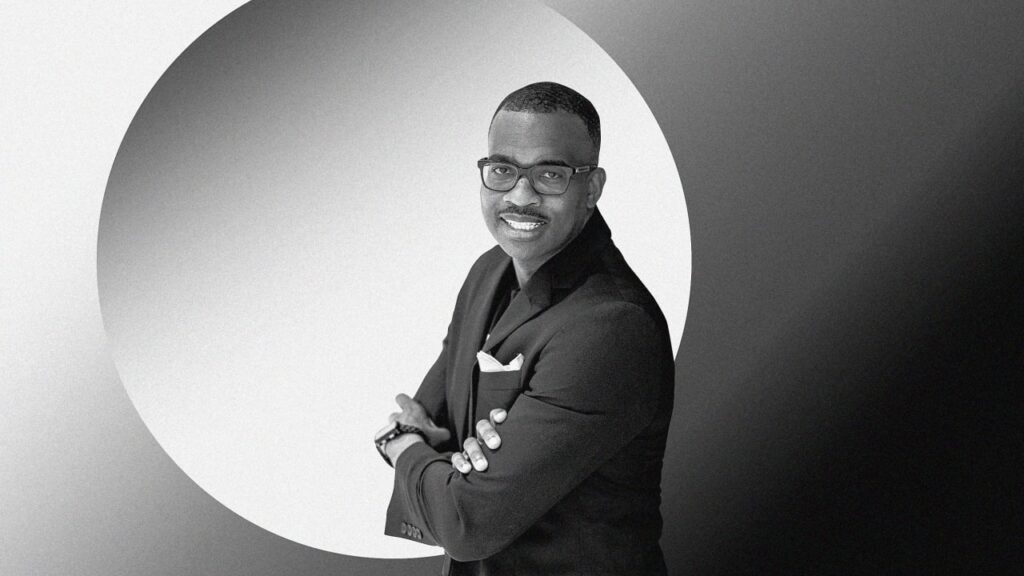

When Joel Castón was nominated for Washington, D.C.’s Sentencing Fee in December, he was elated. Two years after his launch from jail, the place he spent 27 years out and in of 16 services, he was trying ahead to the chance to be part of the dialog about how individuals are sentenced within the nation’s capital.

However on January 2, he acquired phrase of a letter from U.S. Attorney Matthew Graves condemning the nomination. Graves argued that “neither [Castón’s] work nor his lived expertise as an incarcerated particular person renders him an skilled in sentencing coverage issues” and that his coverage stances would likely align with a member of The Sentencing Project who was already on the fee.

Castón isn’t any stranger to the discrimination confronted by individuals who have been incarcerated, however he and his fellow advocates argue that removed from being a legal responsibility, it’s exactly their expertise with the felony authorized system that makes them an asset.

Castón really gained his first election—to D.C.’s Advisory Neighborhood Fee—when he was nonetheless incarcerated. He says he was astonished by what number of headlines had been extra desirous about the truth that he was convicted of homicide on the age of 18 than the truth that he’d made historical past as the primary presently incarcerated particular person to win workplace in D.C. “Of us gravitate towards [my conviction] as a result of we’ve got a preconceived notion of what ‘a assassin’ seems like,” he says. “It’s nearly as in the event that they’re programmed to seek out it problematic to talk about my accolades in a constructive mild with out mentioning the darkest second in my previous.”

Castón just isn’t alone. “Serving [in political office] is like strolling by means of 1,000 microaggressions a minute,” says Washington State Consultant Tarra Simmons. “Typically I simply get outright hate, together with many dying threats.” Simmons grew to become a lawyer after serving a 30-month sentence with the Federal Bureau of Prisons. However, as soon as launched, legally representing individuals like her wasn’t sufficient—she needed to alter the legal guidelines that she says criminalize issues like poverty, race, and substance use whereas additionally responding to mistreatment and inequity inside services (like working dangerous jobs for little or no pay).

Since being elected in 2021, she has pushed for elevated wages for incarcerated individuals (she labored for simply 42 cents an hour); advocated for grants that help voting outreach inside jails; launched a invoice that can enfranchise individuals in Washington prisons to vote; and is working with native judges on a reform invoice that would offer the chance for sentences to be reconsidered after 10 years. (Washington State presently doesn’t enable parole.)

However Simmons says that whereas it’s been difficult, for each naysayer, there’s a rising neighborhood of supporters who see the significance of lived expertise in management, significantly in the case of political illustration. Amongst these is Simmons’ former Home seatmate, Senator Drew Hansen, who’s preventing totally free calls in jail amid heightened costs. “He referred to as me the opposite day and mentioned, ‘Tarra, that is a part of your legacy—I might by no means have gotten into these points however for you.’”

On February 6, the D.C. Council unanimously voted Castón onto the Sentencing Fee. The vote substantiated the various letters of help that got here in following Graves’ letter—from those that had been incarcerated with and mentored by Castón to organizations like Fwd.us and The Sentencing Project. The latter’s codirector of analysis, Nazgol Ghandnoosh, has been on D.C.’s Sentencing Fee for a yr and believes that Castón’s distinctive understanding of the sentencing course of is a step in the fitting course for the District and the bigger motion for illustration.

For Ghandnoosh, Castón, and others impacted by incarceration “have a degree of perception that researchers, judges, police chiefs—none of us can supply: What does it imply to have lived in a neighborhood disproportionately impacted by crime? What does it imply to get a yr sentence versus probation? What does it imply for somebody to be in jail for 20-plus years? How destabilizing is that? What’s it wish to have your dad and mom cross away when you’re incarcerated? That is essential data that will actually profit us as a metropolis.”

Along with introducing new laws to help communities impacted by incarceration, it’s simply as invaluable to debate what laws these in workplace can forestall. Final yr, a invoice got here throughout Rhode Island Consultant Cherie Cruz’s desk that will restrict individuals’s skill to problem their conviction, referred to as post-conviction aid, to 1 yr after sentencing. As somebody who was capable of expunge her file 20 years after her wrongful conviction, this was private. She believes the consultant who sponsored the invoice didn’t absolutely notice its affect. Figuring out that post-conviction aid can “change the panorama for somebody with a file,” because it did for her, she succeeded in stopping the invoice.

There has lengthy been a motion to humanize and empower these impacted by incarceration, though our present system has, in Castón’s phrases, “systemically ostracized, criminalized, demonized, and disenfranchised us since slavery.” Castón, Cruz, and Simmons are part of a rising motion of individuals instantly impacted by incarceration who’re operating for workplace and dealing to alter the system from the within. They’re joined by different previously incarcerated leaders like Councilmember Yusef Salaam and Assemblymember Eddie Gibbs in New York; Speaker Don Scott in Virginia; Consultant Leonela Felix in Rhode Island; and different members on Sentencing Commissions in Minnesota and North Carolina. The truth is, Simmons cocreated a political motion committee referred to as Actual Justice WA to help previously incarcerated individuals who need to run for workplace.

This coalition of political leaders is increasing, and but it’s not a monolith; every particular person brings a singular perspective. “Many imagine that previously incarcerated individuals all vote the identical, all suppose the identical manner—we’ve been put in the identical proverbial field,” Castón says. However he says the expertise doesn’t preclude individuals’s skill to be neutral. “Being previously incarcerated doesn’t imply that I lack the capability or the power to be simply and equitable in my judgment. I need to show that somebody with my background can serve.”

[ad_2]

Source link