[ad_1]

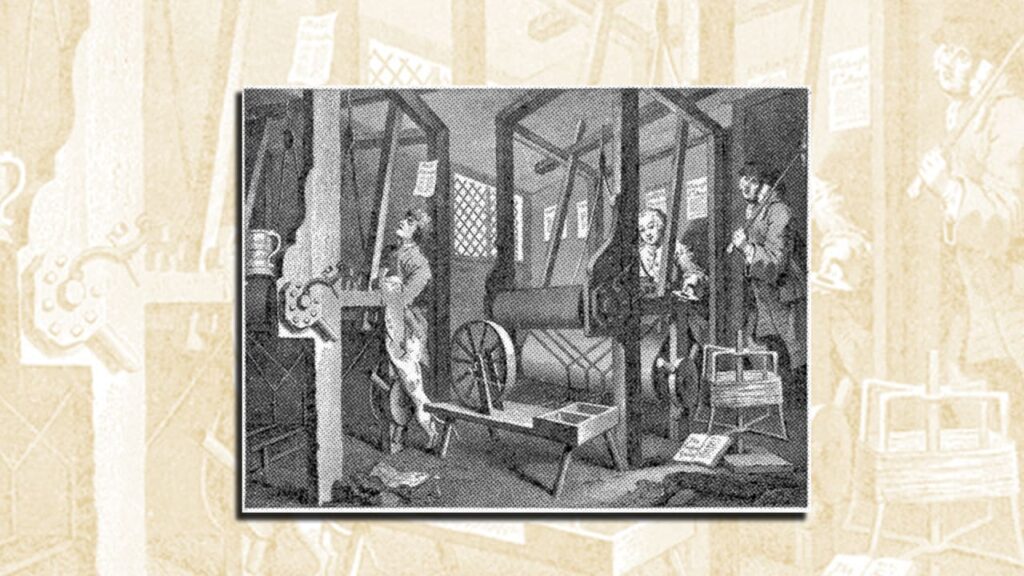

The time period Luddite emerged in England in the early 1800s. On the time there was a thriving textile business that relied on handbook knitting frames and a talented workforce to create fabric and clothes out of cotton and wool. As the Industrial Revolution gathered momentum, nevertheless, steam-powered mills threatened the livelihood of hundreds of artisanal textile employees.

Confronted with an industrialized future that threatened their jobs and their skilled id, a rising variety of textile employees turned to direct motion. Galvanized by their chief, Ned Ludd, they started to smash the machines that they noticed as robbing them of their supply of earnings.

It’s not clear whether or not Ned Ludd was a real person, or just a figment of folklore invented throughout a interval of upheaval. However his identify turned synonymous with rejecting disruptive new applied sciences—an affiliation that lasts to this present day.

Questioning know-how doesn’t imply rejecting it

Opposite to widespread perception, the original Luddites were not anti-technology, nor had been they technologically incompetent. Quite, they had been expert adopters and customers of the artisanal textile applied sciences of the time. Their argument was not with know-how, per se, however with the ways in which rich industrialists had been robbing them of their lifestyle.

At this time, this distinction is usually misplaced.

Being referred to as a Luddite typically signifies technological incompetence—as in, “I can’t determine learn how to ship emojis; I’m such a Luddite.” Or it describes an ignorant rejection of know-how: “He’s such a Luddite for refusing to make use of Venmo.”

In December 2015, Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk, and Invoice Gates had been collectively nominated for a “Luddite Award.” Their sin? Elevating considerations over the potential risks of synthetic intelligence.

The irony of three outstanding scientists and entrepreneurs being labeled as Luddites underlines the disconnect between the time period’s authentic which means and its extra fashionable use as an epithet for anybody who doesn’t wholeheartedly and unquestioningly embrace technological progress.

But technologists like Musk and Gates aren’t rejecting know-how or innovation. As an alternative, they’re rejecting a worldview that every one technological advances are finally good for society. This worldview optimistically assumes that the sooner people innovate, the higher the long run will probably be.

This “move fast and break things” strategy towards technological innovation has come below rising scrutiny in recent times—particularly with rising consciousness that unfettered innovation can lead to deeply harmful consequences {that a} diploma of accountability and forethought might assist keep away from.

Why Luddite concepts matter within the age of AI

In an age of ChatGPT, gene enhancing, and different transformative applied sciences, maybe all of us must channel the spirit of Ned Ludd as we grapple with how to make sure that future applied sciences do extra good than hurt.

In reality, Neo-Luddites or New Luddites is a time period that emerged on the finish of the twentieth century. In 1990, the psychologist Chellis Glendinning printed an essay titled “Notes Toward a Neo-Luddite Manifesto.”

In it, she acknowledged the character of the early Luddite motion and associated it to a rising disconnect between societal values and technological innovation within the late twentieth century. As Glendinning writes, “Just like the early Luddites, we too are a determined individuals searching for to guard the livelihoods, communities, and households we love, which lie on the verge of destruction.”

On one hand, entrepreneurs and others who advocate for a extra measured strategy to know-how innovation lest we stumble into avoidable—and probably catastrophic dangers—are often labeled “Neo-Luddites.”

These people symbolize specialists who consider within the energy of know-how to positively change the long run, however are additionally conscious of the societal, environmental, and financial risks of blinkered innovation.

Then there are the Neo-Luddites who actively reject fashionable applied sciences, fearing that they’re damaging to society. New York Metropolis’s Luddite Club falls into this camp. Fashioned by a gaggle of tech-disillusioned Gen Zers, the membership advocates using flip telephones, crafting, hanging out in parks, and studying hardcover or paperback books. Screens are an anathema to the group, which sees them as a drain on psychological well being.

I’m unsure what number of of at present’s Neo-Luddites—whether or not they’re considerate technologists, technology-rejecting teenagers, or just people who find themselves uneasy about technological disruption—have learn Glendinning’s manifesto. And to make sure, components of it are relatively contentious. But there’s a frequent thread right here: the concept that know-how can result in private and societal hurt if it isn’t developed responsibly.

And perhaps that strategy isn’t such a nasty factor.

Andrew Maynard is a professor of superior know-how transitions at Arizona State College.

[ad_2]

Source link